On Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels

05 Jan. 2023 - Long Beach, CA

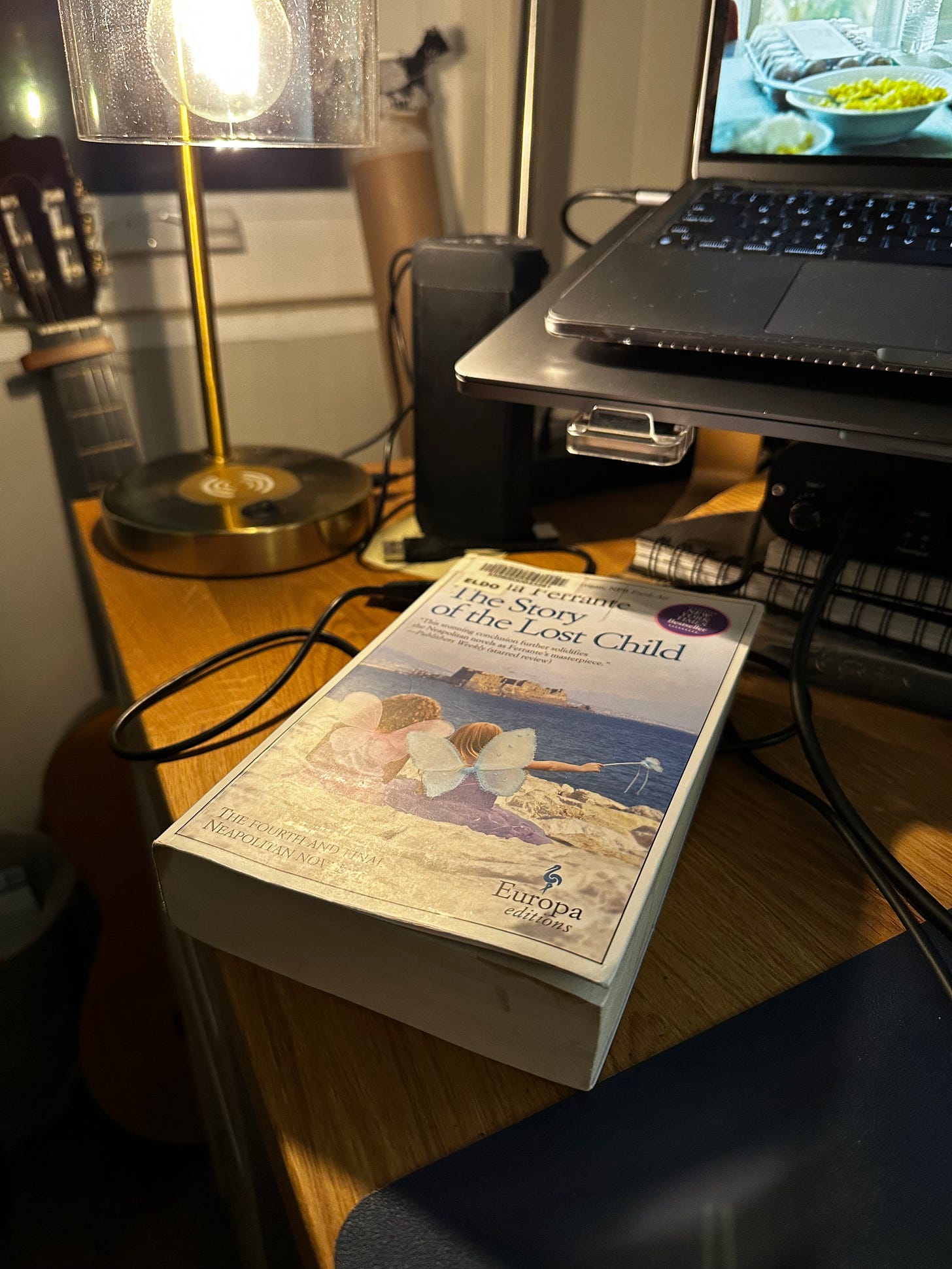

As I began to turn over the final of page of The Story of the Lost Child, I felt a wave of silent nostalgia and grief overwhelm me. I gave myself a moment to stare at the final paragraph resting on page 473 to prolong it just a little longer, almost in disbelief that my time with Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels was about to come to an end. For 2 months, I was nestled up with these books, growing up with Lenù and Lila as if they were my own estranged friends, enamored with Ferrante's cosmic writing style in stunning and selective detail.

I truly believe these books are a story about time itself, and how we as people are its mere occupants with many, many grievances. Ferrante writes with such an intimate force, thrusting me into her boundless world and immersing me within every layer of inferno that has been carefully laid out in it, until it is no longer distinguishable from my own. From Italy’s volatile political backdrop to the neighborhood watch in Naples, Ferrante has created a dense mosaic of her country, and it’s easy to get lost. But Lenù and Lila's paradoxical friendship from childhood to old age, in the swirling sandstorm that is Ferrante's time, is the emotional glue that bounds and grounds me to her Italy, keeps me from being swept away by the winds, and helps me stand back. That at once contemptuous and compassionate friendship between two women, kindled out of feminine survival in a patriarchal culture and society, speaks to our complexity as people trying to make sense of this chaotic, unorganized, and boundless world. Her depiction of love can be symbiotic, strange, and even appalling, and yet they fill the voids in these broken women shattered by an unstable and hypermasculine world. Each emotional and relational detail builds upon the other, so that we can fully understand Ferrante’s world for what it is, her characters for who they are. These novels are so densely human; they've thrilled me, broken my heart, and wrapped it back up with a ribbon. Through this connection, I can begin to look inward.

I spent each book exploring and journeying through my phases of estranged grief, seeking peace and solace by the paradoxical act of relishing in the anger, chaos, love, and pain that Ferrante conjures in her pages. I sought comfort and understanding with myself in these books, even in the ugliest parts, so that I can feel that I was part of this routine, that I was a pinball smacked around and bouncing off of person to person like Lenú. As I close The Story of the Lost Child for the last time, I am left feeling like I am leaving a toxic friendship; I know that it must end, but I can't help occasionally missing the routines that came with it, warts and all. I am left now reminiscing on the good moments, seething at the bad ones, glimmering at the hopeful ones, and pondering in the telling ones. I am thinking of my time.

.