Why Did You Move To New York?

31 May, 2024 - Williamsburg, Brooklyn, NY

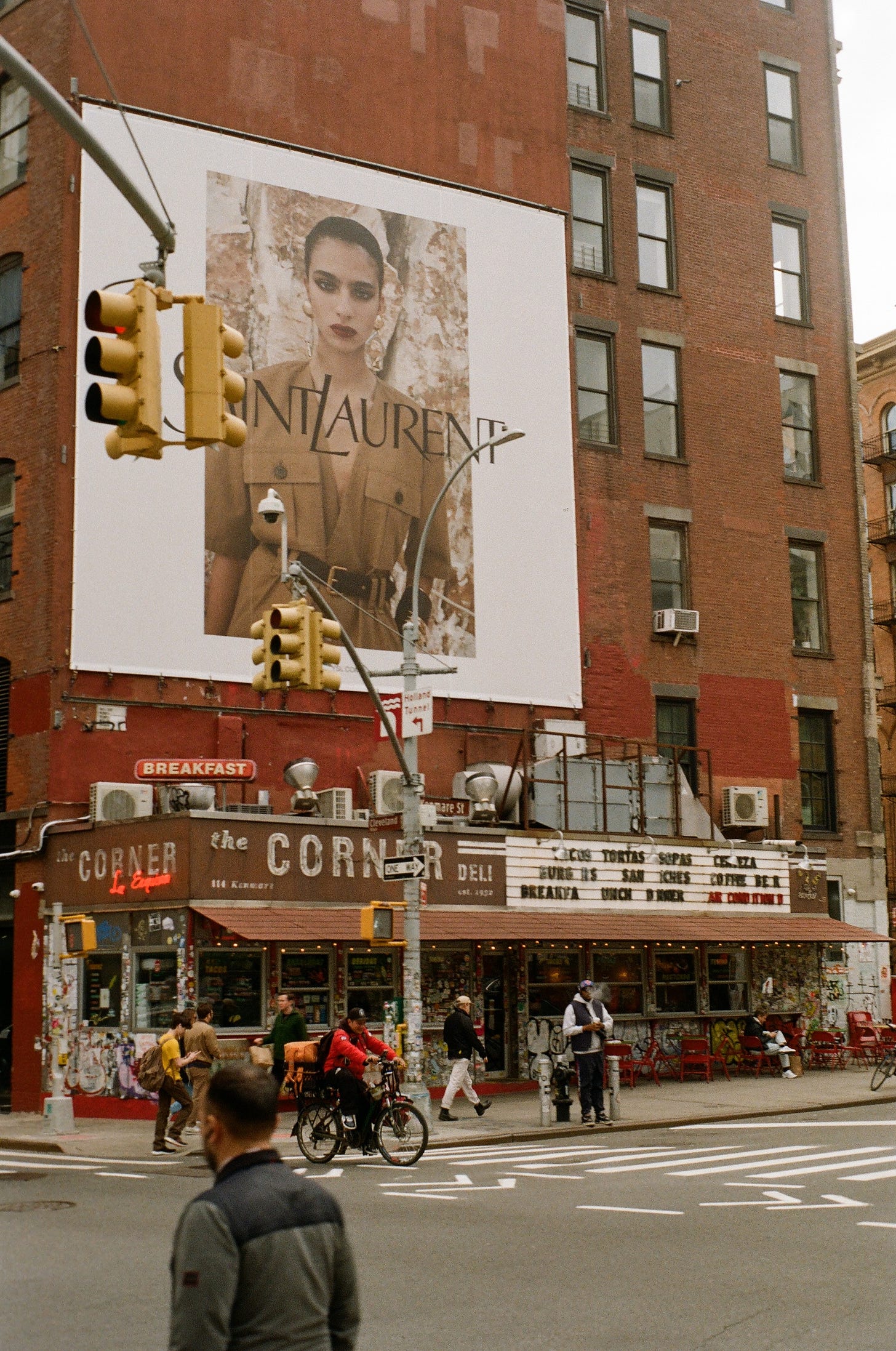

You moved to Brooklyn to become perfect, ideally. You maximize every opportunity to seize each day, to squeeze every last drop of sunshine that drapes over the skyscrapers and pools into the shadows of avenues and streets below. Otherwise, how could you justify leaving the home you had in California if it only amounts to the same business as usual, just with proper seasons and a more humid atmosphere; what use is a hermit’s life in the Big Apple when that hermit is a homebody? You came here to be different, to let the city change you, so you go out, every day and every night, to let it change you.

You scour the Internet for concerts, shows, book events, bars, restaurants, anything that can let this day and night not go to waste, any form of momentary distraction from the impending doom of boredom seeping in the walls of your Williamsburg apartment. No opportunity should be lost in The City That Never Sleeps. You want to be one thing and everything in this city, combing through and laying a claim or a stake on any scene that piques your interest.

The first thing you want to be is a great, classic, New York jazz musician. You go to jam sessions, and get to know every name of every person that graces the stage with you for one jazz standard. You tell them two things: that you enjoyed playing with them (even if it’s quite possible you didn’t, but mostly because you didn’t think you played well enough for them), and your Instagram handle, so you can message them later about other jazz jam sessions happening in the city.

You find your groove (pun intended), regularly going to jam sessions in Bed-Stuy on Thursdays and near home in East Williamsburg on Sundays, both hosted by the same cool-headed saxophonist who simply loves to play, bar to bar, and gets paid doing it, bar to bar. In his vaguely East Coast accent, he gets you on for your two tunes for the night. And each time you join in, you suck. You’re just noodling on stage, playing random scales thinking you can fake it until you make it, but you know this well-seasoned audience can see through your harmonic bullshit. You don’t know the jazz standards these cats are calling and cooking, you lose your place, you forget what chord you’re on, what section, how to fucking play a piano in a bar in Brooklyn.

This is a learning opportunity, you tell yourself, playing with others. But your piano doesn’t sound better - it sounds like the same noodles, over and over, over a bass and a drum, drowned out by a horn that plays lines more fun than yours. The jam sessions become less and less a lesson and more a session of exposure therapy, settling in with the idea that you might just be not good. You learn to be comfortable with being mediocre, even when you know you can be better. The host grants you the courtesy of shouting you out by name after your two tunes, asking for your last name each and every time because he forgets it as easily as he forgets your playing. You are resigned to be forgotten.

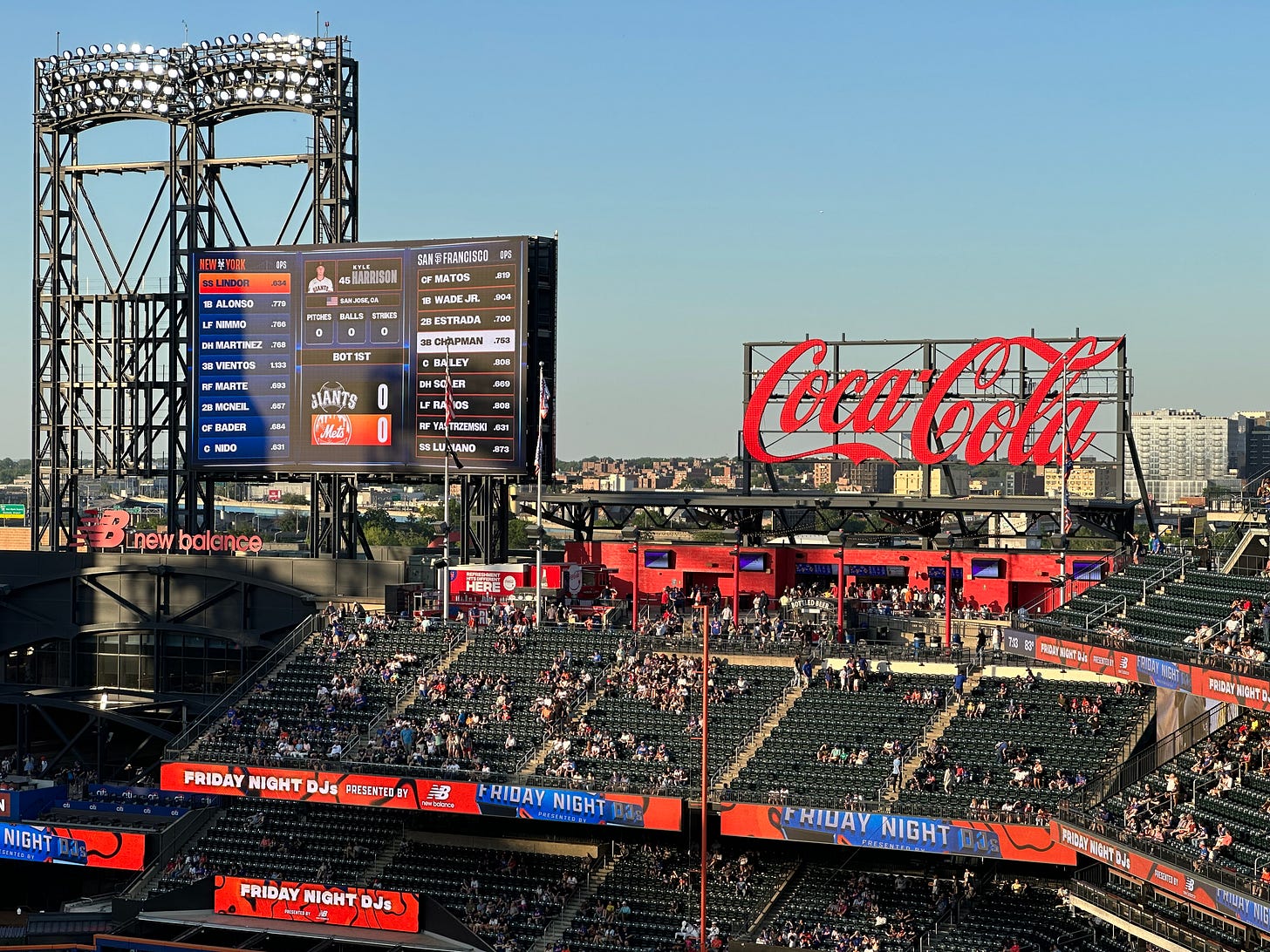

Every night is ripe with opportunity to go out and claim a piece of the Big Apple; just today, a book event and a concert you really want to attend are on the same night, so you make it work and rush between F trains to make both (You wish you had one of those time machines to help you be at both places at once), but admit that it would have been easier if you just committed to one of them. You are overwhelmed with decision paralysis, the inherent sacrifice that comes with committing to one plan and plane of existence over another, the debilitating FOMO (fear of missing out) that plagues your active choice to be in this city, every day.

You question whether these were the right things to do, whether this is the right path to the growth you imagined you’d go through when living in the city. You thought that you’d pull off the reverse-Hollywood dream, and move to the East Coast to be that cool jazz musician that your friends said you’d be, who absorbed the metropolitan culture rampant throughout the city, to be a 3-hour step ahead of your past life in California. You engineered your itinerary, manufacturing a routine that statistically could have put you ahead of your best possible self, a fool-proof plan. But this feels like a bricked dead end, walled in like the tight apartment buildings sitting above every Brooklyn coffee shop and clothing store and weed shop, a rude awakening that your skills and interests that made you feel like hot shit in the West Coast were just vestiges of a plateauing mediocrity in a city full of professionals. The city was breaking you rather than making you, hollowing you out of any sense of self or individuality. But you remember the old wives’ tale, taking it to heart and applying it to the City That Never Sleeps: you can’t grow unless you sleep more.

You start seeing a therapist. Your new therapist, who you are only allowed to see within New York state lines, listens to you ramble about your fears of being forgotten, of missing out, of weighing every decision so heavily, and assures you that decisions are temporary; you can always go back to California, he asks you, but what’s keeping you here? What and why do you fear missing out?

There’s a lingering reflection, that you wish you could see the future, that you can predict and chart out your surefire path to thrive here and take your cultural riches back to the Bay Area when you’ve eventually had enough of the Empire State. Every decision and thing you do here in this city is an expression of that preemptive anticipation, to plan ahead and treat every chance as your last and only one. Every action and reaction is a permanent stamp on the timeline of your aura in New York, each one altering your trajectory through the city’s five boroughs. Or, so, this is what you believe.

You remind yourself of how your therapist likened the consequences of decisions to waves: they come in and retract, leaving behind some remnants on the shore, but passing through time and states of being. The hardest part is trying to accept the ability to anticipate these waves as they come, while simultaneously accepting the inability to see the entire ocean of possibility.

So you learn how to swim. Through your weekly earnest networking at jazz jam sessions, you hit up the house pianist and ask her for lessons. On your first lesson in her studio in Crown Heights, she listens to you ramble about your love for Bill Evans, eventually getting you to finally articulate what you’re hoping to achieve as a musician in New York. In a simple word, you say “fluency” and reflect on how your solos and improvisations feel like mixolydian gibbering on the piano, nonsensical musical noodling that rambles with the changes. She says this only once to you, “If you feel like you’re not getting better, it’s likely because your standards are too high.” Pondering over perfection created a self-fulfilling prophecy of imperfection, her words helped you realize. Then she has you play on her out-of-tune, rickety upright, resonating within the caverns of the brick cove.

Together, you take the classic jazz tune “On Green Dolphin Street” and apply wacky prompts to it per her suggestion, such as, “Play the ‘Dolphin” melody in an entirely different key” or “Solo on it but have each measure start on the 3 of each chord” or “Play a melody line in each key for your solo.” These are imperfect solos on an imperfect pitch, but they are musical linguistic building blocks for perfect practice.

As you repeatedly practice these lines over her kinetic bass line, you realize that everything you’ve been trying to do in this city is to strive for this imaginary ideal of perfection, to shape an identity that so many have seemed to develop when they came and gone through over the years. This was, unfortunately, the standard that was too high™, impeding on your path to any form of greatness. Your standards need to be lower if you hope to grow higher, as you began to take each practice little by little.

You go back to the bar’s Sunday jam session a new imperfect man, where the saxophonist host is seated at the doorway as he’s letting a flutist belt out their solo over a standard. He greets you with a flick of his open hand and an eyebrow raise, though you’re not sure if this is a hesitant greeting masking the dread of seeing you here, given your track record of fumbling tunes. No matter. After 30 minutes of tunes, you get called up. The band calls Isfahah, a Duke Ellington chart that you, *gasp*, do not know! But you read the charts and it gets easier and easier each cycle, and you miraculously stay with the changes, just like the simulations in Crown Heights. It’s time to solo, so you remember what the house pianist showed you: start on the 3s, build off of your licks, and create something out of those. Your solo could be better, but you managed to play through the changes twice; not bad for a tune you just learned on the spot!

This gives you enough confidence to call out “On Green Dolphin Street” after the flutist’s suggestion for a bossa nova tune isn’t received by the rhythm section so well. After playing through the tune a few times, you suppress the temptation to change keys, alter the rhythm, play the licks that you kept practicing over and over again. But when your solo comes, the drummer makes that decision for you. He beams at you, and switches the beat to, funny enough, a bossa nova one. You vibe really well with this, and build your solo around this new groove he’s imposing on you, sweeping through scales and bouncing along to the sonic mountains you’re building together. For the first time at one of these jam sessions, you smile.

You also want to be a writer, because that’s what New Yorkers do when they’re not San Franciscans. And you’re a New Yorker now. Your work’s W-2 form has you listed as paying taxes to ‘NY’, and all your mail goes here now; it’s official. When it’s time to start thinking about writing your next blog post, you decide to write it in the second-person, mostly because David Foster Wallace’s run-on sentences in Infinite Jest and Viet Thanh Nguyen’s memoir A Man of Two Faces have been rubbing off on you, but also because it’s another practice prompt for your scribe skills. As you continue writing, the second-person voice allows you compartmentalize your outer-body anxieties, to keep the stressors at bay and in the hopes that you’ll champion them. You reflect on the wealth of memories that sit within the sediment of just two weeks, stacked and packed with life lessons and experiences that form the skeleton of your ideal Brooklyn life, ultimately dictated by a mindset rather than an active plethora of lifestyle choices. There is solace in remembering and writing that there is always the option to rest in the restless city, to take a step back and ride each of the waves.

Good one, Ethan. You will keep developing in all ways.